I think we have this view of ancient justice which suggests it was entirely cruel and unusual. Kill someone? Death. Get into a fight? Death. Steal a pear? Death. No understanding of the context or the relative harm caused, unlike in our supposedly enlightened age.

The truth is rather different. While some societies could be very cruel, God’s laws were not. In this passage, God addresses a variety of crimes of different severity, and the penalties for each.This passage not only helps us understand the way our own legal system is structured, but how we think about the value of life and justice in a world where justice is imperfect at best.

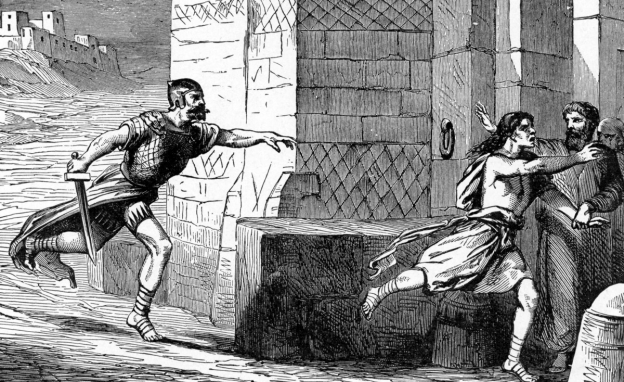

The first group of crimes described involve capital punishment (vv.12-17). The general principle was “whoever strikes a man so that he dies”, violating the Sixth Commandment, should be sentenced to death (v.12).

But there were circumstances where death was not appropriate. For instance, where the death was unintentional (v.13), what we call manslaughter, then death was not inevitable. The offender could flee to designated cities of refuge, where the case was investigated.

If guilty of murder (but attempting to escape justice), his sentence was death (v.14). However, if the killing was unintentional, the sentence was effectively commuted to a period of internal exile (cf. Numbers 35).

The next example related to offences against parents, the foundation of social order (Fifth Commandment). Attempted murder of parents merited the death penalty (v.15). Likewise, someone who cursed (effectively repudiated) their parents was also liable to death (v.17).

Finally, to kidnap someone and sell them into slavery, or possess a kidnapped person sold into your hands, attracted the death penalty (v.16). This killing of a person’s freedom is an assault on their image-bearing nature.

The second group of crimes discussed are crimes of assault (vv.18-27). The first example is a disagreement which flares into a fight involving fists and weapons, leaving one party injured. This required compensation of lost earnings and costs of healing (vv.18-19).

Sometimes a master would beat a slave as punishment. If the slave died, then the master died too (v.20). However, if the slave died later, there was no compensation, because the slave worked for the master: so he had harmed himself (v.21).

If a pregnant woman is injured in a fight (eg, a bystander), then if serious injury fell to the mother or child, the offender suffered severely in proportion to harm (vv.23-5). But if there was no ultimate harm then a fine was imposed (v.22).

Finally, injury to a slave causing permanent harm resulted in immediate freedom (vv.26-7). A master’s right to punish a slave was not absolute, and if he abused his slaves, then he too suffered immediate economic hurt for his acts.

The final group of crimes are those of negligence, often involving animals (vv.28-36). In the first example, an animal with no history of violence attacks causing death (v.28). The animal would be destroyed and not eaten, since it had taken life and was ritually unclean. No penalty fell on the owner besides loss of property.

But if the animal was a known aggressor, then not only was the animal killed, but the owner (v.29) for negligence. In some circumstances, the owner may have been able to pay a high ransom to avoid death (v.30).

The same principles applied whether it was “a man’s son or daughter” (v.31). The same value applies to people, as bearers of God’s image (Gen 1:26-28). When a slave was the victim, the animal must still be stoned, but the slave’s master is also due restitution for the price of a slave (v.32).

If someone failed to cover a well or pit into which an animal fell to their injury or death, the negligent person had to pay restitution to the owner (vv.33-4).

Finally, if two animals fought and one was killed, each party shared the cost (v.35). However, if one animal was a known aggressor, then the negligent owner suffered the cost alone (v.36).

In all of these situations, the sentence is proportionate to the crime and the loss. This is the true meaning of “an eye for an eye” (v. 24). Lesser crimes carried lesser penalties, crimes involving death carried greater sentences. But many of these punishments were focused on making things right… at least, as much right as possible in a sinful world.

This principle exists in our laws today. We reserve the worst sentences for murderers, while lesser crimes carry lesser sentences. These crimes and punishments remind us that everyone is worthy of dignity and respect, and justice when wronged.

Sadly justice in our world is imperfect, as Jesus himself was killed despite his innocence. But in God’s justice, the world’s injustice against Christ satisfied God’s justice for the sin of his people, and led to mercy for many, including us.

So instead of demanding vengeance for wrongdoing against us, perhaps we should seek mercy, and leave justice to God.